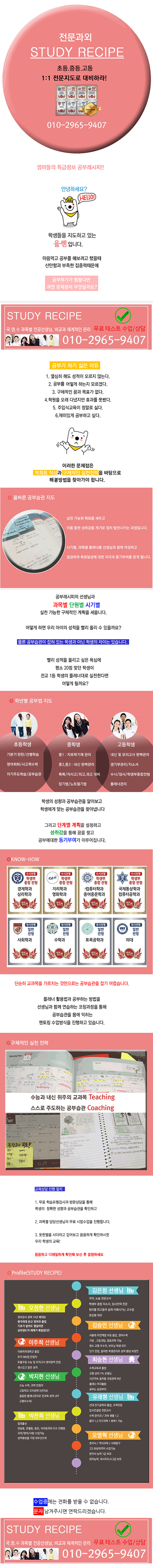

성사동에서 학생들과 함께 수업을 진행하고 있는 멘토교사입니다.

"morning again in America," regarding the recovering economy and the dominating performance by the American athletes at the 1984 Summer Olympics on home soil, among other things.[30] He became the first U.S. president to open an Olympic Games.[242] Previous Olympics taking place in the United States had been opened by either the vice president (three times) or another person in charge (twice). Reagan's opponent in the 1984 presidential election was former vice president Walter Mondale. Following a weak performance in the first presidential debate, Reagan's ability to perform the duties of president for another term was questioned. His confused and forgetful behavior was evident to his supporters; they had previously known him to be clever and witty. Rumors began to circulate that Reagan had Alzheimer's disease.[243] Reagan rebounded in the second debate; confronting questions about his age, he quipped: "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience". This remark generated applause and laughter, even from Mondale himself.[244] That November, Reagan won a landslide re-election victory, carrying 49 of the 50 states. Mondale won only his home state of Minnesota and the District of Columbia.[129] Reagan won 525 of the 538 electoral votes, the most of any presidential candidate in U.S. history.[245] In terms of electoral votes, this was the second-most lopsided presidential election in modern U.S. history; Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1936 victory over Alf Landon, in which he won 98.5 percent or 523 of the then-total 531 electoral votes, ranks first.[246] Reagan won 58.8 percent of the popular vote to Mondale's 40.6 percent. His popular vote margin of victory—nearly 16.9 million votes (54.4 million for Reagan to 37.5 million for Mondale)[247][248]—was exceeded only by Richard Nixon in his 1972 victory over George McGovern.[129] Second term Reagan is sworn in for a second term as president by Chief Justice Burger in the Capitol rotunda Reagan was sworn in as president for the second time on January 20, 1985, in a private ceremony at the White House. To date, at 73 years of age, he is the oldest person to take the presidential oath of office. Because January 20 fell on a Sunday, a public celebration was not held but took place in the Capitol rotunda the following day. January 21 was one of the coldest days on record in Washington, D.C.; due to poor weather, inaugural celebrations were held inside the Capitol. In the weeks that followed, he shook up his staff somewhat, moving White House Chief of Staff James Baker to Secretary of the Treasury and naming Treasury Secretary Donald Regan, a former Merrill Lynch officer, Chief of Staff.[249] War on drugs Main article: War on drugs In response to concerns about the increasing crack epidemic, Reagan began the war on drugs campaign in 1982, a policy led by the federal government to reduce the illegal drug trade. Though Nixon had previously declared war on drugs, Reagan advocated more aggressive policies.[250] He said that "drugs were menacing our society" and promised to fight for drug-free schools and workplaces, expanded drug treatment, stronger law enforcement and drug interdiction efforts, and greater public awareness.[251][252] In 1986, Reagan signed a drug enforcement bill that budgeted $1.7 billion (equivalent to $4 billion in 2019) to fund the war on drugs and specified a mandatory minimum penalty for drug offenses.[253] The bill was criticized for promoting significant racial disparities in the prison population,[253] and critics also charged that the policies did little to reduce the availability of drugs on the street while resulting in a tremendous financial burden for America.[254] Defenders of the effort point to success in reducing rates of adolescent drug use which they attribute to the Reagan administrations policies:[255] marijuana use among high-school seniors declined from 33 percent in 1980 to 12 percent in 1991.[256] First Lady Nancy Reagan made the war on drugs her main priority by founding the "Just Say No" drug awareness campaign, which aimed to discourage children and teenagers from engaging in recreational drug use by offering various ways of saying "no." Nancy Reagan traveled to 65 cities in 33 states, raising awareness about the dangers of drugs, including alcohol.[257] Response to AIDS epidemic According to AIDS activist organizations such as ACT UP and scholars such as Don Francis and Peter S. Arno, the Reagan administration largely ignored the AIDS crisis, which began to unfold in the United States in 1981, the same year Reagan took office.[258][259][260][261] They also claim that AIDS research was chronically underfunded during Reagan's administration, and requests for more funding by doctors at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) were routinely denied.[262][263] By the time President Reagan gave his first prepared speech on the epidemic, six years into his presidency, 36,058 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS, and 20,849 had died of it.[263] By 1989, the year Reagan left office, more than 100,000 people had been diagnosed with AIDS in the United States, and more than 59,000 of them had died of it.[264] Reagan administration officials countered criticisms of neglect by noting that federal funding for AIDS-related programs rose over his presidency, from a few hundred thousand dollars in 1982 to $2.3 billion in 1989.[265] In a September 1985 press conference, Reagan said: "this is a top priority with us...there's no question about the seriousness of this and the need to find an answer."[266] Gary Bauer, Reagan's domestic policy adviser near the end of his second term, argued that Reagan's belief in cabinet government led him to assign the job of speaking out against AIDS to his Surgeon General of the United States and the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services.[267] Addressing apartheid From the late 1960s onward, the American public grew increasingly vocal in its opposition to the apartheid policy of the white-minority government of South Africa, and in its insistence that the U.S. impose economic and diplomatic sanctions on South Africa.[268] The strength of the anti-apartheid opposition surged during Reagan's first term in office as its component disinvestment from South Africa movement, which had been in existence for quite some years, gained critical mass following in the United States, particularly on college campuses and among mainline Protestant denominations.[269][270] President Reagan was opposed to divestiture because, as he wrote in a letter to Sammy Davis Jr., it "would hurt the very people we are trying to help and would leave us no contact within South Africa to try and bring influence to bear on the government". He also noted the fact that the "American-owned industries there employ more than 80,000 blacks" and that their employment practices were "very different from the normal South African customs".[271] As an alternative strategy for opposing apartheid, the Reagan Administration developed a policy of constructive engagement with the South African government as a means of encouraging it to move away from apartheid gradually. It was part of a larger initiative designed to foster peaceful economic development and political change throughout southern Africa.[268] This policy, however, engendered much public criticism and renewed calls for the imposition of stringent sanctions.[272] In response, Reagan announced the imposition of new sanctions on the South African government, including an arms embargo in late 1985.[273] These sanctions were, however, seen as weak by anti-apartheid activists, and as insufficient by the president's opponents in Congress.[272] In August 1986, Congress approved the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which included tougher sanctions. Reagan vetoed the act, but the veto was overridden by Congress. Afterward, Reagan reiterated that his administration and "all America" opposed apartheid, and said, "the debate ... was not whether or not to oppose apartheid but, instead, how best to oppose it and how best to bring freedom to that troubled country." Several European countries as well as Japan soon followed the U.S. lead and imposed their sanctions on South Africa.[274] Libya bombing Main article: 1986 United States bombing of Libya British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (here with Reagan in 1986) granted the U.S. use of British airbases to launch the Libya attack. Relations between Libya and the United States under President Reagan were continually contentious, beginning with the Gulf of Sidra incident in 1981; by 1982, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was considered by the CIA to be, along with USSR leader Leonid Brezhnev and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, part of a group known as the "unholy trinity" and was also labeled as "our international public enemy number one" by a CIA official.[275] These tensions were later revived in early April 1986, when a bomb exploded in a Berlin discothèque, resulting in the injury of 63 American military personnel and death of one serviceman. Stating that there was "irrefutable proof" that Libya had directed the "terrorist bombing,"